28 Dec 2020

The Reverse Fade: Repainting, Repointing, or a Legacy of Black & White Photography?

Following some initial comments on the theme in my last post about Hovis signs around London, I’ve been pondering more the apparent phenomenon of the ‘reverse fade’ i.e. when a ghost sign appears to become more visible over time.

I posted the above before and after picture of the Hovis sign to social media (Twitter, Instagram) and received a variety of responses to the question of what is going on between 1957 and today. Many concurred with my initial hypothesis that the sign was at some point overpainted, and that this whitewash has then faded to reveal what’s beneath. However, others offered up some interesting alternative explanations.

Over-Painting

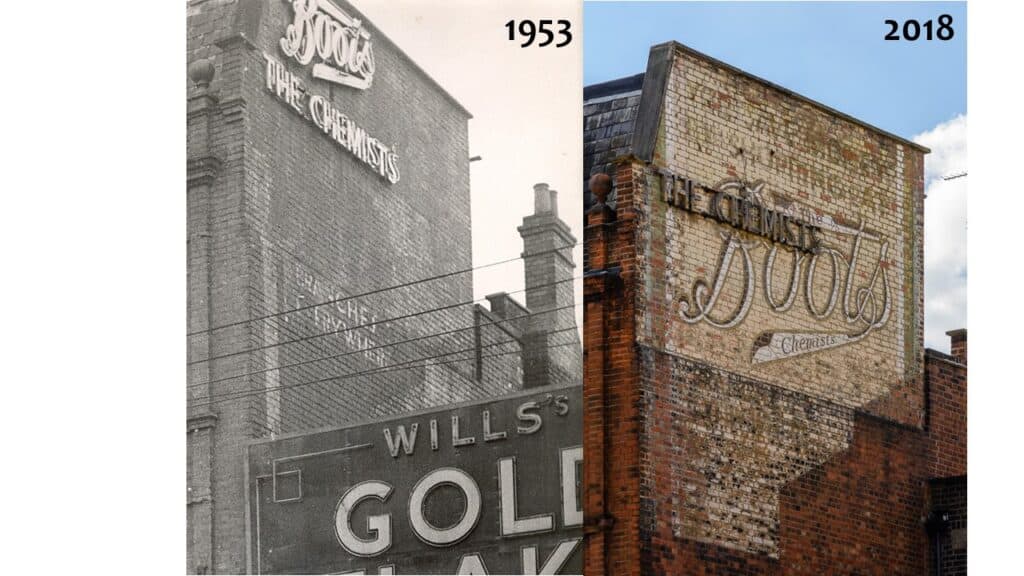

In the case of the Boots sign, there is evidence and a justification for the over-painting of the older sign. The shop was inside that building 1932–69 but by 1953 the painted sign had been replaced with a more modern illuminated piece. In order to avoid the clashing of old and new layers of lettering, the old sign was painted out. It is ironic that the once-redundant painted sign is now back and holding up well against its successor which only partially remains.

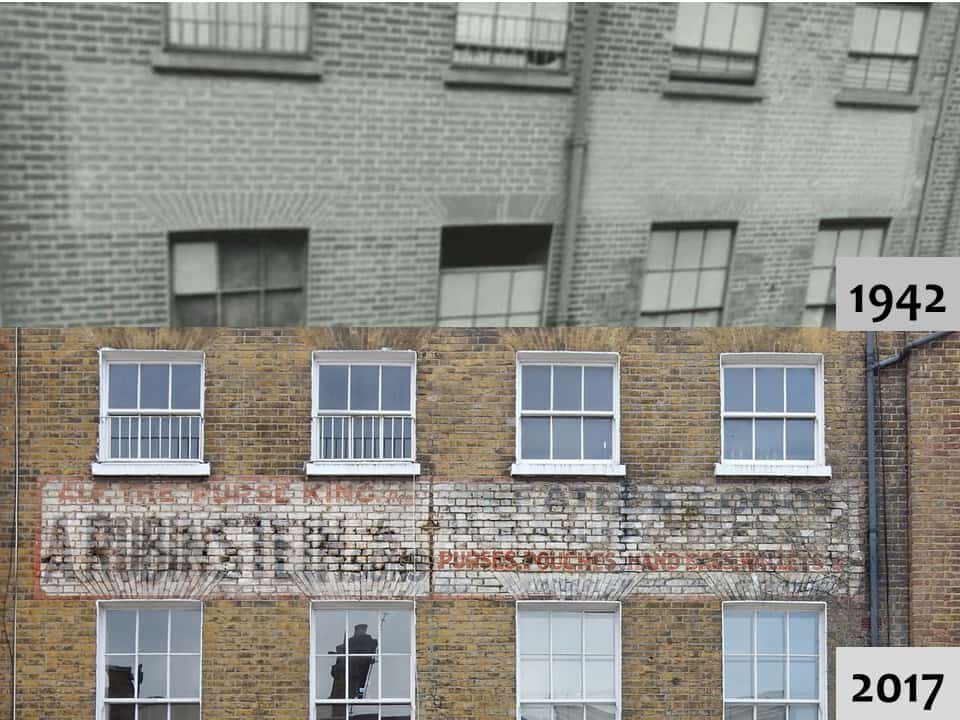

Similarly, with the Rubinstein on Stoke Newington Church Street. The business had disappeared from the area by 1929 but the 1942 photo shows no traces whatsoever of the sign. Later images from the 1980s showing it becoming visible again. This seems to be another cast iron case of over-painting.

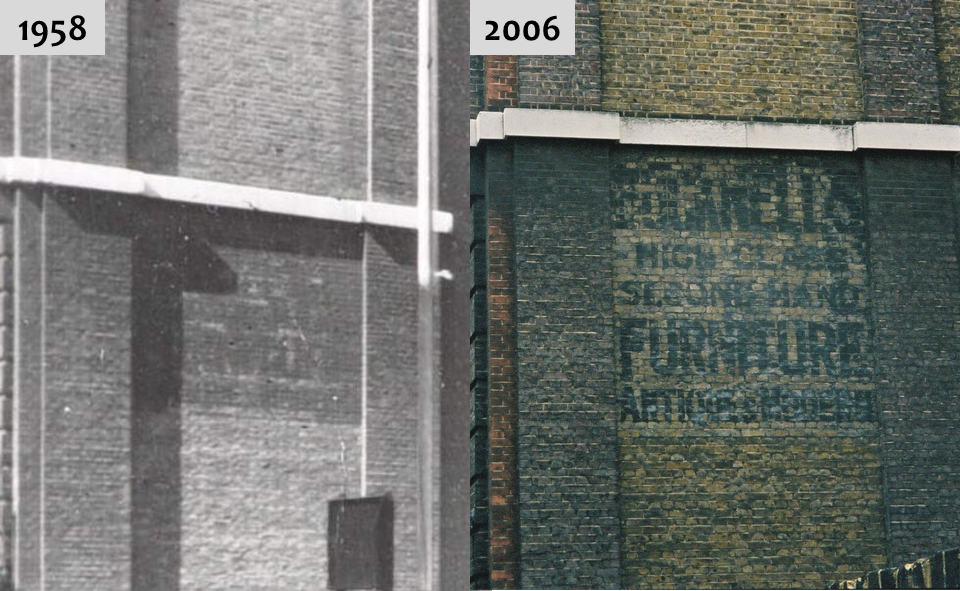

The last example above is for Bucknells on Riding House Street and this one is less clear cut. The reduced legibility of the sign in 1958 could be due to over-painting, or simply the build up of dirt which was later cleaned.

In each case the quality of the paints used on the older signs appears to have affected their longevity. Although I’ve never had a scientific explanation of why, it is largely touted that the old lead paints actually permeated the porous brick and cured over time to become structurally part of it. This would help to explain why in cases like the Redferns Rubber Heels sign in Islington the chemical treatment and cleaning of later layers painted with non-leaded paints has little or no impact on the older sign.

Repointing

Based on the above examples from elsewhere, the over-painting theory would also hold weight for the Islington Hovis sign. It dates from when the bakery there was occupied by Bernard George Wittick, 1922–1939. In the 1957 photo the building is housing D. O’Hara Sports, and it wouldn’t be surprising for them, or some other occupant in the intervening 18 years, to paint out the legacy signage.

One of the other suggestions for the effect in this particular instance is the effects of repointing, especially if this was done with lime mortar. In fact, as Nick Perry points out on Instagram, it could have in fact been a bit of both i.e. a whitewashing, followed by a repointing.

“The whitewash will have lightened the rough mortar more than the brick, and in the 50s photo is at the stage where the bright mortar is quite distracting. By the time it’s faded from the mortar too, the contrast is much lower and the detail more discernible.”

Changing Photographic Technology

Another explanation could lie in the way that black and white photography deals with certain tones versus colour photography, or even the use of filters to achieve certain effects. While filters can’t be ruled out, it seems unlikely to have been the impact of wider technological factors. Roy Reed notes that:

“Before 1906 all B&W photography was orthochromatic (only sensitive to blue light). A photo of the union flag will show the red parts as black and the blue as light grey. After 1906 panchromatic film was introduced.

By 1926 the price of pan film equalised with ortho, so after that date most photos would have been equally sensitive to all colours and given a more ‘natural’ tonal range.”

The Jury is Out

It seem that the evidence in the case of the Islington Hovis sign is inconclusive and that the effect could be due to over-painting, repointing, or some combination of both. I would be interested in any other views based on the evidence presented, and also in getting to the bottom of the chemical/physical properties of lead paint that have ‘led’ to so many signs enduring.